Fighting for Richard Nixon’s Legacy 50 Years After His Resignation

My tribute to a great president and an even greater friend...

50 years ago today, President Richard Milhous Nixon made his resignation official in a letter to Secretary of State Henry Kissinger.

Nixon had served a total of 2,026 days as the thirty-seventh president of the United States before he left the White House on August 9, 1974.

While to most, he was a former President, to me he was a friend and mentor who I am blessed beyond belief to have known.

That’s why I felt the need to write this piece today — to give you a glimpse into the man I knew, and to explain why his legacy is worth preserving even today.

If you like what you read, I do hope you consider subscribing here at Stone Cold Truth, where I regularly post content like this, and that you share this article if you feel so inclined.

President Richard Nixon had three distinct periods in his life: His rise, his fall, and his rise again.

To begin his story, I will begin with the lowest moment in his life, which undoubtedly were the days and weeks following him resigning the presidency.

Nixon biographer Jonathan Aitken writes:

During the early months after his resignation Nixon was a soul in torment. He spent days shut away behind the guarded walls of his Oceanside, CA, home. He made a brave show of keeping up appearances while he deteriorated both emotionally and physically to the point where he had close calls with a nervous breakdown and with death.

At the same time Nixon told Sen. Barry Goldwater that rumors that he had lost the will to live were “bullshit!”

Aitken goes on to write that Nixon made efforts “to remain presidential without the Presidency.”

Each morning he arrived in his office at 7 AM prompt, immaculately dressed in coat and tie despite the 100-degree heat. He was guarded by a detail of eighteen Secret Service men, given medical attention by Navy corpsmen; provided with transport by the marines and supplied with secure communications by the Army. He was attended upon by a retinue of some twenty assistants, aides and secretaries who had volunteered to accompany him to California.

But there was essentially no business to be done. Rod Ziegler, his former press secretary, sat with him alone for hours each day with nothing to do but discuss pending lawsuits and plot battle over public control of the White House tapes.

Although Nixon was originally allocated $850,000 by the House of Representatives to fund his move to California and transition to post-presidential life, Congress reduced this amount to only $200,000, which was to be used to cover the costs of office rent and salaries for his team of staff for a period of six months.

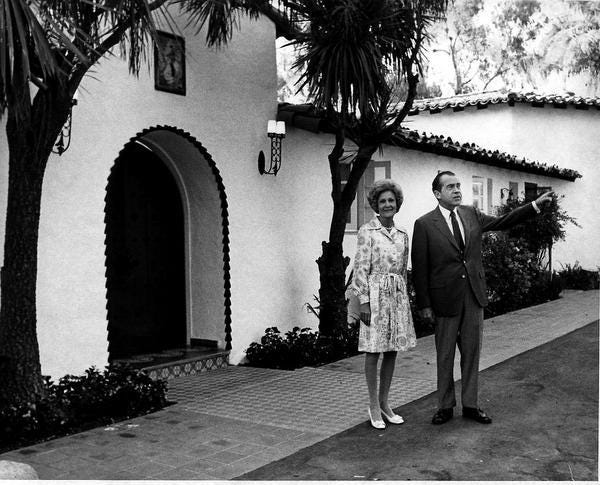

Nixon moved his small staff to California to be near his beloved La Casa Pacifica, a property he purchased in 1969 that became his presidential retreat, christened, “the Western White House.” The property was found for the president in 1969 by a young White House aide instructed by Nixon to go to California and find a suitable presidential retreat.

It was there that I first spent substantial time with the former President. When I was elected Young Republican National Chairman in 1977 he invited me for lunch — which became dinner and a day of talking politics. By 1980 Nixon had moved to New York and one of my assignments in the Reagan campaign was to brief Nixon weekly on the campaign’s progress — sometimes at his home at the Upper East Side of Manhattan — other times at his office at 26 Federal Plaza downtown.

During better financial times, Richard and Pat Nixon purchased the private Spanish-styled estate as a sanctuary where they could entertain dignitaries and run the business of the United States in a secure and serene environment, and as a private place to conduct his presidential duties outside of Washington. It remained a hub for international negotiations both in his presidential and post-presidential years. Breshnev, the Soviet leader, would call on Nixon at his post-presidential retreat.

In 1974, Nixon became sick with phlebitis in his left leg, a blood-clotting disorder that causes veins to be inflamed. Doctors told him that he needed to be operated on or he could possibly die. He chose the operation. The illness just happened to be around the time that his former Chief of Staff Bob Haldeman, along with White House Counsels John Dean and John Ehrlichman were on trial.

Nixon was subpoenaed to testify but, by chance, he was granted a dismissal by the presiding judge, who trusted the ailment was not just a ruse after three court-appointed lawyers examined him and said he was in no current condition to testify. Others were skeptical of the timing of his illness and accused the former president of faking the ailment so he didn’t have to go to court.

After the presidential pardon, Nixon released the following statement:

I was wrong in not acting more decisively and more forthrightly in dealing with Watergate, particularly when it reached the stage of judicial proceedings and grew from a political scandal into a national tragedy. No words can describe the depth of my regret and pain at the anguish my mistakes over Watergate have caused the nation and the presidency, a nation I so deeply love, and an institution I so greatly respect.

If anyone thought Nixon was grateful for the pardon by Ford, they were mistaken. As Ford struggled to fend off a challenge from Ronald Reagan in the snows of New Hampshire, Nixon announced he would travel to China at the invitation of Chairman Mao.

Nixon’s visit would only serve to remind voters of Ford’s pardon of his predecessor. It was the last thing Gerald Ford wanted in the news. Ford’s lawyers, however, were fighting Nixon’s efforts to get control of the papers and records that he believed were legally his. Nixon was furious about it.

John Sears, former Deputy Counsel to Nixon, who was now working for Reagan, had urged Nixon to take the trip. “He didn’t need much convincing” he told me. The Chinese cooperated in order to signal their lack of happiness with Ford. It was a terrible blow to Ford.

A 1976 article in the Washington Post about that year’s presidential campaign managers stated — probably on the basis of an interview with Sears — that Nixon continued to call Sears for advice, even during his Watergate troubles. Monica Crowley, who served as Nixon’s assistant after his presidency, wrote that Nixon and Sears were still in touch, even though Sears may have played a key role in Nixon’s downfall by helping shape the Watergate narrative through Carl Bernstein and other major reporters.

Sears’s role in Watergate was based on loyalty to the Nixon he knew: the wise man, the teacher, the father figure. Sears’s own father had perished in a fire when Sears was young. Sears revered Nixon as the gold standard of political calculation.

The Nixon with whom Sears had signed up was a man capable of understanding and championing great policies. White House Counsel Len Garment’s book claiming John Sears was Deep Throat is simply wrong. USA Today’s Ray Locker’s book Haig’s Coup makes an open and shut case that General Alexander Haig is Deep Throat — not Mark Felt as, Woodward and Bernstein claim.

This was not the Nixon Sears saw in the self-imposed clutches of the aforementioned Haldeman and Ehrlichman, or of his former Secretary of State Alexander Haig and Special Counsel Charles Colson.

Sears’s loyalty was to Nixon’s ideas and his own sense of public service, honed in long conversations with the Nixon he remembered. The Nixon he helped take down was not the same man.

Ford’s re-election prospects also took a hit from Nixon White House Counsel John Dean.

Dean appeared on the Today television show to publicize his book, aptly titled Blind Ambition. NBC was interested in publicizing his book too. They had just bought the television rights to it.

In the course of his interview, John Dean announced a new “fact” about Watergate:

House Minority Leader Gerald Ford, at President Nixon’s instigation, had successfully squelched the Patman investigation of the financing of the Watergate break-in.

Dean’s charge was essentially true, and Ford’s adamant denial did little.

Nixon was plagued with lawsuits that dragged on almost throughout the rest of his life. These civil suits wore him down emotionally and drained his liquid assets. He seized the opportunity to make some quick cash by writing his memoirs.

Dean’s treachery and lies in the entire Watergate affair are documents here:

Legendary agent Swifty Lazar negotiated a $2 million advance. Nixon would ultimately go on a prolific writing spree that included the writings of ten post-presidential books on domestic policy and international affairs and, of course, his memoirs.

Beyond writing books, Nixon also sought out other public relations opportunities that he thought would earn him some money and allow him to spin his version of Watergate. One of those opportunities came in 1976: the Frost interview.

A few years after Nixon resigned, he was approached by British talk show host David Frost who proposed doing a paid interview show that would delve deep into the Watergate scandal and finally ask the questions that America, and the rest of the world, wanted answered.

Frost paid him $600,000 for a taped interview. The show received fifty million viewers when it aired in 1977. It was one of the highest-rated shows of all time. The show helped Nixon out of his desperate financial situation, but more importantly, it helped improve his image around the world, although Frost got Nixon to go further in atoning for Watergate than others had.

After the Frost interview, Nixon seemed reinvigorated and wanted to jump back into international travel and foreign affairs — the two cards he would use to reinvent himself yet again as a foreign policy expert.

Isolated from his daughters and their husbands as well as their grandchildren on the East Coast, he and Pat soon began looking for properties to buy that were closer to “the fast track.” New York City would be their next move.

In 1980, Richard and Pat Nixon sold their beloved La Casa Pacifica property so they could move to New York City and be closer to the hub of politics and business on the East Coast.

He sold the California estate to the founder of a pharmaceutical company, who also happened to be a big Republican donor who later developed the surrounding parcels of land into residential homesites to create a community now called Cotton Point Estates.

When it was reported that Nixon sold his California home, the General Services Administration of the US Government demanded that the ex-president reimburse them in the amount of $703,367 for items that were installed on the La Casa Pacifica property for post-presidential operations and security.

The GSA claimed the items were abandoned by Nixon when he moved, and the costs for those upgrades now needed to be repaid.

These items that Nixon had installed were a $6,600 gazebo, a $13,500 heating system, $217,006 for lighting and electronics, $137,623 for landscaping, $2,300 for a flagpole, in addition to many other upgrades to the house that were installed by the Secret Service and other government contractors for security and to facilitate the operations and duties of an ex-president.

Nixon refused the demand by the General Services Administration and countered with a public notice for the agency to remove the unwanted items and restore the home to its original condition within sixty days. He also sent a check to the GSA for $2,300 for repayment of the flagpole fee. Nixon claimed the Secret Service insisted on the upgrades to the property. His belligerence paid off, and the GSA desisted.

Finding suitable housing accommodations in New York City for the ex-president and his wife would be a tricky task.

The first co-op that the presidential couple wanted to purchase on Madison Avenue didn’t want the exposure that a disgraced ex-president would bring to the building, so they were denied admittance.

The couple was also denied the ability to purchase another choice New York City property after the building residents joined forces and voted to deny Richard and Pat Nixon’s application for residency.

George Leisure told a reporter at the time, “Everyone signed against them. Money’s not enough here.”

On August 10, 1979, the Nixons found a townhouse to buy at 142 East Sixty-fifth Street, on the Upper East Side, for $750,000, next door to David Rockefeller and other notable power brokers. It was a more suitable location for a man who was accustomed to socializing with world leaders.

Nixon became famous for his late nocturnal “walks” on the Upper Eastside of Manhattan, often stopping for coffee with one lonely Secret Service man at several different diners for coffee.

After only eighteen months in New York City, the Nixons sold their townhouse and bought a home in Saddle River, New Jersey, where they had found a home within a peaceful community that was away from the big, loud, and crowded city and that also afforded them quick and easy access to both Washington, D.C., and New York City.

Pat and Richard Nixon entertained visiting kings, foreign ambassadors, and, most importantly, their grandchildren in their Saddle River home.

The GSA provided office space at 26 Federal Plaza in Manhattan.

Nixon would ultimately give up his Secret Service protection, saving taxpayers millions. Given his well-known aversion to the press, it was surprising that Nixon asked me to arrange a series of small dinners with select reporters for background discussions on politics and foreign affairs.

“I want guys who don’t remember [Alfred] Hiss,” Nixon told me, referring to the Soviet spy who was exposed by then-Congressman Nixon in 1948.

Nixon published his memoir, RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon, in 1978, the first of ten books he was to author after leaving the White House.

This was followed by a series of foreign policy tomes that outlined Nixon’s views on the future of US relations with Russia, China, and the Middle East.

Nixon visited the White House in 1979, invited by President Jimmy Carter for the state dinner honoring Chinese Vice Premier Deng Xiaoping. Carter initially refused to invite Nixon, but Deng said he would visit Nixon in California if the former president was not invited.

Nixon had a private meeting with Deng and visited Beijing again in mid-1979.

When the former Shah of Iran died in Egypt in July 1980, Nixon defied the State Department, which intended to send no US representative, by attending the funeral. Though Nixon had no official credentials, as a former president he was seen as the US presence at the funeral of an ally.

Throughout the 1980s, Nixon maintained an ambitious schedule of speaking, writing, and foreign travel. He met with many third-world leaders.

He joined Presidents Ford and Carter as US representatives at the funeral of Egyptian President Anwar Sadat.

On a trip to the Middle East, Nixon made his views known regarding Saudi Arabia and Libya, which attracted significant US media attention.

Nixon journeyed to the Soviet Union in 1986, and on his return sent President Reagan a lengthy memorandum containing foreign policy recommendations and his personal impressions of Soviet Leader Mikhail Gorbachev.

Nixon connected with Soviet reformer Boris Yeltsin after the fall of the Iron Curtain. Yeltsin aide Michael Caputo told me, “Yeltsin was getting political advice from Nixon on what to do in the former Soviet Union and in the US.” They were on the phone constantly. Yeltsin sent messages to Clinton through Nixon.

During one trip to Moscow, Nixon had a meeting and long discussions with Russian leader Mikhail Gorbachev.

When he came back to the United States, Nixon reported to President Ronald Reagan in a long and detailed memorandum to explain his findings and to offer his suggestions for future diplomatic relations between America and the Soviet Union.

Reagan depended on Nixon’s experience and knowledge of world matters.

Nixon wrote in his memoirs, “I felt that the relationship between the United States and the Soviet Union would probably be the single most important factor in determining whether the world would live at peace during and after my administration. I felt that we had allowed ourselves to get in a disadvantageous position vis-a-vis the Soviets.”

The Washington Post ran stories on Nixon’s “rehabilitation.”

In 1986, Nixon was ranked in a Gallup poll as one of the ten most admired men in the world. Around this time Nixon gave a tour-deforce speech to the American Newspaper Publishers Association.

Political pundit Elizabeth Drew wrote, “Even when he was wrong, Nixon still showed that he knew a great deal and had a capacious memory, as well as the capacity to speak with apparent authority, enough to impress people who had little regard for him in earlier times.” Washington Post publisher Katherine Graham shook Nixon’s hand and ordered a three-page spread called the “Sage of Saddle River.”

Although Nixon had served as a back-channel foreign policy and political advisor for Ronald Reagan, his contacts with President George H. W. Bush, whose ascendency he aided, were minor and formal.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union and the emergence of China, Nixon set his sights on a dialogue with President Bill Clinton, who eventually defeated Bush in 1992.

Nixon understood the delicacy of the situation. He couldn’t invite himself. He had to finagle Clinton into an invitation. He sent the message through Senator Bob Dole and Democratic strongman Robert Strauss.

These efforts were met with frustration, as Clinton was described as noncommittal when approached. That meeting was far more difficult to arrange than might be thought.

At this point, I will step aside and let veteran newsman Marvin Kalb, who was a good friend and solid journalist, tell the story in his book, The Nixon Memo:

Ever since Clinton's election in November 1992, Nixon had been trying to see Clinton and ingratiate himself with the new administration. He realized that it would not be easy. Nixon and Clinton were poles apart in experience, in outlook, and in ideology. Nixon was a Cold War Republican, Clinton a baby-boomer Democrat. Nixon expanded the American war in Southeast Asia, Clinton marched in protest against it. Nixon personified Watergate, Clinton’s wife had worked for Nixon’s impeachment on the staff of the House Judiciary Committee. Still, Nixon wrote Clinton a long, substantive, and thoughtful letter of congratulations. And in a November 19, 1992, op-ed piece in the New York Times, he praised Clinton for ‘aggressively addressing a number of important issues during the transition period.’

But if Nixon expected a quick response, he was to be disappointed. Shortly before Clinton’s inauguration, in mid-January 1993, Nixon resumed his effort to make an impact on the president-elect. He got Roger Stone to send an “urgent” message to Clinton — that the situation in Russia was “very grave” and that Clinton was not getting the “straight story” from the State Department, principally, Nixon said, because Baker was a roadblock. Again, there was no response from Clinton or any of his aides.

Immediately after the inauguration, Nixon, undaunted, sent another “urgent” message to Clinton. This time Stone used Richard Morris, a pollster from Arkansas, as his intermediary. Stone told me that the Nixon message contained three points and what can only be construed as a whiff of political blackmail. First, Stone said that Clinton would find Nixon’s perspective on Russia to be “valuable.” Second, a Nixon-Clinton meeting would “buy” the president a “one-year moratorium” on Nixon criticism of his policy toward Bosnia and other matters. And third, a Clinton-Nixon meeting would generate Republican support for aid to Russia and possibly for a budget compromise on Capitol Hill. Stone continued, ‘Morris told the Clintons that if Nixon was received at the White House, he couldn’t come back and kick you in the teeth.’

A few days later, on the eve of Nixon’s February 1993 visit to Moscow, according to Stone, Morris called him and said that Clinton had agreed in principle to a meeting with Nixon, but no date had been set. Another week passed. Nixon, in Moscow, had met with Yeltsin and promised action. Stone called James Carville and Paul Begala, two of Clinton’s closest political advisers, and urged that a date be fixed, especially since now Clinton could also benefit from a Nixon briefing on his meeting with Yeltsin. Begala immediately saw the political advantages of a meeting. In his mind there was no point in antagonizing Nixon, not when so much of the Clinton program rode on a degree of GOP cooperation on Capitol Hill.

Prodded by Stone, Begala rode herd on the matter of the meeting. He told John Podesta, who managed the traffic flow into the Oval Office, to make certain that the three-point Nixon message reached the president’s desk. ‘You really ought to call him,’ Begala advised. Yes, Clinton agreed, but again nothing happened.

For his part, as days passed with no call from the White House, an increasingly frustrated Stone encouraged Nixon to ‘bludgeon” Clinton in much the same way as he had Bush. During the Vietnam War, as president, Nixon had employed a tactic that French journalist Michel Tatu labeled “credible irrationality,” Nixon’s way of frightening the North Vietnamese into believing that he would be capable of doing anything to achieve his ends and they had better be accommodating. In this spirit he let Stone spread the word in Washington that he was losing his patience. Stone called Tony Coelho, a former Democratic congressman from California with superb contacts at the White House, and warned that Nixon was on the edge of exploding. The situation in Russia was desperate. Nixon had ideas—and a short fuse. Could Coelho help arrange a Nixon meeting with Clinton? The implication was clear: a meeting would buy time, information, and maybe cooperation; further delay would buy upheaval in Russia and political confrontation at home.

Nixon also sniffed the political and journalistic winds and figured that, along with the private pressure, it was time for him to go public again. He decided that another ‘shot across the bow,’ as Stone put it, was now in order. It was to be a warning shot at the new administration that Nixon had to be recognized as a player in policy deliberations on Russia and Yeltsin. Once again, the shot was to be fired from the op-ed page of the New York Times. Stone later recalled warning his White House contacts that the ‘piece could be gentle or not so gentle.’”°

When I approached both James Carville and Paul Begala, solid practitioners of the political craft and friends, they both said the president was receptive and said he would reach out to the thirty-seventh president. But the call did not come. Clinton advisor Dick Morris learned that Hillary was blocking the initiative, and it was Morris who would break the logjam by arguing that protocol would eliminate Nixon as a critic of the administration if he was received in a respectful way and that Clinton’s liberal bona fides allowed him to safely reach out to the ex-president. “If only Nixon can go to China, only Clinton can invite Nixon,” Morris successfully argued. Nixon was delighted when the invitation came.

After Nixon’s death, here is what I wrote for The New York Times in 1994:

“So what did you think of him?” I asked Richard Nixon after his first meeting with Bill Clinton.

“You know,” Mr. Nixon replied, “he came from dirt and I came from dirt. He lost a gubernatorial race and came back to win the Presidency, and I lost a gubernatorial race and came back to win the Presidency. He overcame a scandal in his first campaign for national office and I overcame a scandal in my first national campaign. We both just gutted it out. He was an outsider from the South and I was an outsider from the West.”

Thus the 37th President revealed the special kinship he felt with the 42nd, despite their differences in party, philosophy and generation. And Mr. Nixon had a special reason to reach out: he was so deeply committed to the cause of increasing U.S. aid for the emerging republics of the former Soviet Union that he violated his own ironclad rule in dealing with successors—to give advice only when asked.

Mr. Nixon had dark suspicions that Hillary Rodham Clinton was blocking him; in 1974 she had served on the staff of the House committee that recommended impeaching him. More likely, the all-consuming confusion of a new Presidency was to blame. In any event, the call finally did come, and a few days later, on March 8, 1993, the two men met in the living room of the White House family quarters for a long private talk about aid to Russia.

It was a moment Mr. Nixon had foreseen. In 1992 he heard through the grapevine that President George Bush’s strategists were weighing inviting him to the Republican National Convention. Mr. Nixon reviewed his options with me. “I could go to the convention and give a speech praising Bush,” he said, “but that would be boring, and the only thing worse in politics than being wrong is being boring. I could go to the convention and deliver a rip-snorting attack on Clinton. If I do that and Clinton is elected, it would be very hard for me to reach out to him on the situation in Russia.”

Although Mr. Nixon wanted badly to be accepted again at his party’s convention, he issued a statement that afternoon that he would not attend and did not wish to be invited.

In the end, Mr. Nixon came to like Mr. Clinton and had enormous respect for his political talents. “You know that bit he does where he bites his lip and looks like he is pondering the question?” he asked me. “I think it’s practiced, but let me tell you, it’s great television.”

He thought the Whitewater affair could pose serious problems. When I pointed out that the poll numbers reflected no damage to Mr. Clinton’s popularity, Mr. Nixon observed that Watergate had not hurt him either, until the televised Senate hearings. “The American people don’t believe anything’s real until they see it on television,” he said. “When Whitewater hearings are televised, it will be Clinton’s turn in the bucket.”

Perhaps. But if Mr. Nixon’s advice to his young successor provides for a surer American foreign policy and increases the chances of peace, then we all profited more than either of them.

The two presidents forged a solid bond of respect and admiration toward each other during the time Clinton was in office. Nixon often praised him for his political talents, but he thought some of his tactics were staged. He told me, “I think it’s practiced, but let me tell you, it’s great television.”

Nixon blamed Hillary Clinton for blocking his early attempts to meet with the president calling her a “red hot,” a term used to describe extreme leftists in the 1950s.

In 1974, Hillary Clinton was a staff lawyer for the House of Representatives Judicial Impeachment Inquiry Committee, which was responsible for

investigating whether or not there was enough evidence to impeach or prosecute President Nixon for the Watergate affair.

Hillary had been fired for her role in writing fraudulent legal briefs, lying to investigators, and confiscating public documents to hide her deception and conspiring to hinder the defense of Richard Nixon.

“She was out to get me,” the former president told me when he called to brief me on his White House visit. “He [Clinton] really appreciates my help and he’s much smarter than Bush,” Nixon said ebulliently.

Clearly, Nixon thought he was in play again, despite Hillary’s best efforts.

Hillary’s actual role in 1974 bears examination. Hillary began her political career at Yale Law School, where she was a close confidant of her political professor, Mr. Burke Marshall, the chief political strategist for the Kennedys.

Mr. Marshall helped Hillary get her job as a congressional staff lawyer, which then allowed him to place her in the Watergate investigative committee through his close connections to the Democrat chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, Peter Rodino, a congressman from New Jersey.

Hillary’s placement as a House of Representatives lawyer allowed Marshall to then inject her into the Judiciary Committee that was investigating Watergate.

In addition to Hillary, there were two other close allies of Marshall that were also added to the Nixon impeachment inquiry staff to harm Nixon’s defense.

They were John Doar, who was Marshall’s deputy when he was in the Justice Department and whom Rodino appointed as head of the impeachment inquiry staff, and the other was Bernard Nussbaum, who was assistant US attorney in New York and a close friend of Rodino’s.

Nussbaum was placed in charge of directing the investigation into Watergate and Nixon’s potential prosecution. It was a partisan project that Hillary Clinton, a twenty-seven-year-old staffer on the House Judiciary Committee, helped coordinate with senior Democratic leaders to manipulate the political process and strip President Nixon of his constitutional rights to a fair hearing.

Hillary’s boss, Jerry Zeifman, the general counsel and chief of staff to the House Judiciary Investigative Committee during the Watergate hearings, fired Hillary after it was uncovered that Clinton was working to impede the investigation and undermine Nixon's defense.

He told Fox News that “Hillary’s lies and unethical behavior goes back farther — and goes much deeper — than anyone realizes.”

Zeifman maintains that he fired Hillary “for unethical behavior and that she conspired to deny Richard Nixon counsel during the hearings.”

When asked why he fired Clinton, Zeifman responded, “Because she is a liar.” He went on, “She was an unethical, dishonest lawyer. She conspired to violate the Constitution, the rules of the House, the rules of the committee and the rules of confidentiality.”

Zeifman wrote candidly about his encounter with a young Hillary Clinton when she worked for him as a staff lawyer.

He mentioned a number of facts that he thought people should know about how the prospective presidential contender conducts herself.

He said, “Because of a number of her unethical practices I decided that I could not recommend her for any subsequent position of public or private trust.”

Other Judiciary Committee staffers who worked with Clinton, such as Franklin Polk, the chief Republican counsel on the committee, have confirmed many of the details of what Zeifman has reported.

Zeifman stated, “Nixon clearly had right to counsel, but Hillary, along with Marshall, Nussbaum, and Doar, was determined to gain enough votes on the Judiciary Committee to change House rules and deny counsel to Nixon. And in order to pull this off, Hillary wrote a fraudulent legal brief, and confiscated public documents to hide her deception.”

In 2013, Hillary would show her disdain for Nixon in a discussion with an all-woman group over a glass of wine at a restaurant and tavern, Le Jardin Du Roi, near her palatial home in Chappaqua.

“The IRS targeting the Tea Party, the Justice Department's seizure of AP phone records and [Fox reporter] James Rosen’s e-mails — all these scandals. Obama’s allowed his hatred for his enemies to screw him the way Nixon did,” Hillary said.

Where it all started

The story of Richard Milhous Nixon ended where it began — in Yorba Linda, California — the city where he was born and where he was laid to rest. The thought of being buried in his birth town, near his childhood home, kept him grounded.

He often reminisced about how great it was to grow up in the small Orange County, California, town. He felt fortunate to have lived his younger years there.

When he had to make the decision of where his presidential library and museum would be located, there was nothing to ponder. In his mind, it was always going to be Yorba Linda, although some aides tried to convince him to build it closer to his La Casa Pacifica residence in San Clemente, but Nixon knew that he would not own the coastal estate forever.

For him, Yorba Linda was the obvious choice for his presidential museum and library.

Between 1984 and 1990, the Nixon Foundation raised $26 million in private funds to develop the library and museum site. He wanted to build it next door to the small wooden farmhouse that his father built and where the future president had discovered his passion for politics.

The Nixon Foundation is a nonprofit institution that was formed by the former president to fund the construction of his library and to educate the public about the life, legacy, and times of the thirty-seventh president of the United States.

The library was dedicated on July 19, 1990, with the help of three US presidents who served after Nixon who were there to honor the ex-president.

“What you will see here, among other things, is a personal life,” Nixon said at the dedication ceremony. “The influence of a strong family, of inspirational ministers, of great teachers. You will see a political life, running for Congress, running for the Senate, running for governor, running for president three times. And you will see the life of a great nation, 77 years of it—a period in which we had unprecedented progress for the United States. And you will see great leaders, leaders who changed the world, who helped make the world what we have today.”

Inside the museum, the tour began with a timeline of Nixon’s family history and accomplishments then proceeded to show the ex-president, as he was — a complicated, introverted, determined politician and statesman.

Critics claimed the depiction of Nixon’s life and legacy was one-sided and minimized the mistakes of Watergate while emphasizing Nixon’s accomplishments in the foreign and domestic realm.

Each year, the library and museum feature domestic and foreign policy conferences, educational classes for schools, town meetings, editorial forums, and a full schedule of highly acclaimed authors and speakers who discuss government, media, politics, and public affairs.

The museum and library were originally designed, developed, and operated by the private Nixon Foundation, but it is now administered by the National Archives.

The exhibits became much more “balanced” once the National Archives took control in 2007.

The takeover of the presidential library by the National Archives added a lot of content to the museum and library, but it also changed the tone of the exhibits. There is now much more attention to the negative side of Nixon’s career than what the presidential library initially displayed when Nixon’s family and friends were running it.

I think the dispute over content will be a constant and ongoing battle between the Nixon family and the National Archives.

The nine-acre library and museum grounds contain the birthplace and restored childhood home of Richard Nixon, a 3D walkthrough display of twenty-two separate informational galleries, each showcasing a separate part of the president’s life.

There are interactive theaters, a “First Lady’s Garden,” a full-sized replica of the East Room of the White House and a high-tech performing arts center for stage performances and educational seminars. There is also a replica of the Lincoln sitting room and the presidential office — all of which are overlooking a large reflecting pool that is surrounded by an outdoor ceremonial pavilion.

Nixon’s helicopter is also on display. Marine One (also known as Army One if army pilots are in command of the rotorcraft) has been painstakingly restored to its original condition, as it was when it was in service as the presidential helicopter.

It’s the same helicopter that Nixon used on more than 180 trips while serving as president, and then used one last time when he was no longer commander in chief so he could fly home to sunny California, by way of Andrew’s Air Force base in Maryland.

On departure, he boarded the helicopter on the White House south lawn then raised his arms in the victory position, waved to the crowd a fond farewell, and disappeared into the belly of the aircraft.

The sixteen-passenger “Sea King” was used in past administrations by President Kennedy, President Johnson, and President Ford, who all used this same presidential helicopter as their primary mode of airborne transport while in Washington.

It’s a significant piece of aviation history, appropriately placed on permanent display on the grounds of the Nixon Museum.

Surprisingly not among the exhibits is the presidential limousine X-100, which President Kennedy was shot in. Johnson had ordered the limo cleaned inside and out within hours of Kennedy’s death and then had it shipped on November 25 to Detroit for “refurbishment.”

Nixon himself would order the car repainted and used it extensively during his presidency.

Nixon’s association with Camelot, even with the man defeated by it in 1960 would endure.

The library holds over 6 million pages of records, 19,000 still photographs, 150 reels of film, 900 audio recordings of Nixon speeches, plus 3,000 books in addition to the National Archives collection that has recently been added, to include another 42 million pages of records, 300,000 pictures, over 30,000 gifts that were given to Nixon, 4,700 hours of video recordings, and almost 4,000 hours of White House tape recordings.

The presidency of Richard Nixon is probably the most documented of any other president. The movies, pictures, documents, and testimonials that have been retained of Nixon and that are on display at the presidential library and museum provide a rare perspective into the life and personality of a complicated man, who despite his many challenges, rose to the position of leader of the free world.

Resilience

Resilience is the quality that best characterized Richard Nixon.

Just as he began plotting his comeback bid for the American presidency the day after his razor-thin defeat by John Kennedy, I am convinced that Nixon began plotting his final campaign for elder statesman the day after he resigned the presidency in 1974.

In 1960, I taped a Saturday Evening Post cover portrait of Richard Nixon by Norman Rockwell to my bedroom door.

Although I had been a 12-year-old Goldwater zealot in 1964, I began researching the 1960 election and concluded that Nixon had been robbed. I wrote Nixon a letter to his law office in 1967 urging him to run again.

In 1968 I was appointed Chairman of Youth for Nixon in Connecticut by Nixon State Campaign Chairman and Ex-Governor John Davis Lodge, and I got a coveted job as a gofer for Nixon Campaign Manager John Mitchell at the Republican National Convention in Miami Beach.

Although I was a gopher in his 1968 campaign and a very junior aide in his 1972 campaign, it was not until his post-presidential years that I got to know Richard Nixon and was drafted as an operative in his final campaign.

Nixon would have us believe that there was no final campaign for redemption, but in retrospect Nixon’s last campaign was more measured, more painstaking, and more difficult than his comeback bid for the presidency.

I recall riding to midtown Manhattan with Nixon to attend a New York State Republican Party fund-raiser at which Nixon was to be the guest of honor. It was to be his first foray in public for a political event after his resignation, and Nixon was uncertain how he would be received.

Before he opened the car door, he looked me in the eye and said, “I hope this isn’t too soon.”

The event was a triumphant success. Nixon understood that the success of his resurrection would be contingent on his never reaching for an official role and by meting out his opinions on a judicious and measured basis.

“Don’t accept every speaking request and every request for an interview,” he told Jeanne Kirkpatrick when she left federal service. “Speak out only when you have something to say.”

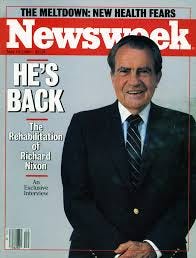

When Nixon charmed Katherine Graham at the newspaper editor’s association luncheon in his post-presidential years, the publisher directed Newsweek to secure an interview for a cover story. It was left to me to negotiate the details.

Nixon agreed, and the interview was scheduled.

When Chernobyl blew up, the Newsweek people said they would run the interview, but would put the Soviet disaster on the cover. Nixon’s directions to me to be forwarded to the editors were firm and precise. No cover — no interview.

The cover ran, with the headline, “He’s Back.”

Nixon knew that he was relegated to a backstage role in American politics, but he played that role with enthusiasm and tenacity.

When Ronald Reagan muffled his first debate with challenger Walter Mondale, Nixon calmly assured Reagan aides that the poll numbers would stabilize, the expectation for Mondale in the second debate would soar, that expectations for Reagan would drop, and that Gipper could put Mondale away with a deft one-liner … And that’s exactly what happened.

After months of badgering George Bush to attend a Soviet-American relations conference that Nixon put together in Washington, DC, Nixon secured Bush’s acceptance and then directed me to leak a memo to the New York Times that outlined Nixon’s belief that the Bush-Baker response to the Soviets need for aid was anemic.

The Times ran with the story, and Bush was forced to haplessly agree with Nixon when he stood up to speak at the conference, where Nixon deftly scheduled Bush to speak immediately after himself.

Taught by his Quaker mother not to display his emotions in public, Nixon was a man who kept his affection deeply in check.

When I married in 1991, Nixon sent my wife and me a leather-bound edition of his book, In the Arena, with the inscription, “To Roger and Nydia Stone—With best wishes for the year ahead,” after which he wrote “Love,” scratched it out, rethought it, wrote it again, and signed, “Richard Nixon.”

I spoke to President Nixon three times in the week before his stroke. He was intensely interested in the political repercussions of the Whitewater affair.

When poll numbers seemed to indicate that the scandal was having little effect on Clinton’s popularity, Nixon pointed out to me that Watergate had little impact on the voters until the televised hearings. “The American people don’t believe anything until they see it on television. Eighty percent of the people receive their news from TV and when the Whitewater hearing is televised it will be Clinton’s turn in the bucket.”

When he died, Richard Nixon was a man content with his place in the world.

Savoring his final victory and his elevation to elder statesman, his books were bestsellers, he received thousands of invitations to speak, the media jockeyed to get his thoughts on the record, President Clinton consulted him on foreign policy matters, and he bathed in the love of his children and grandchildren.

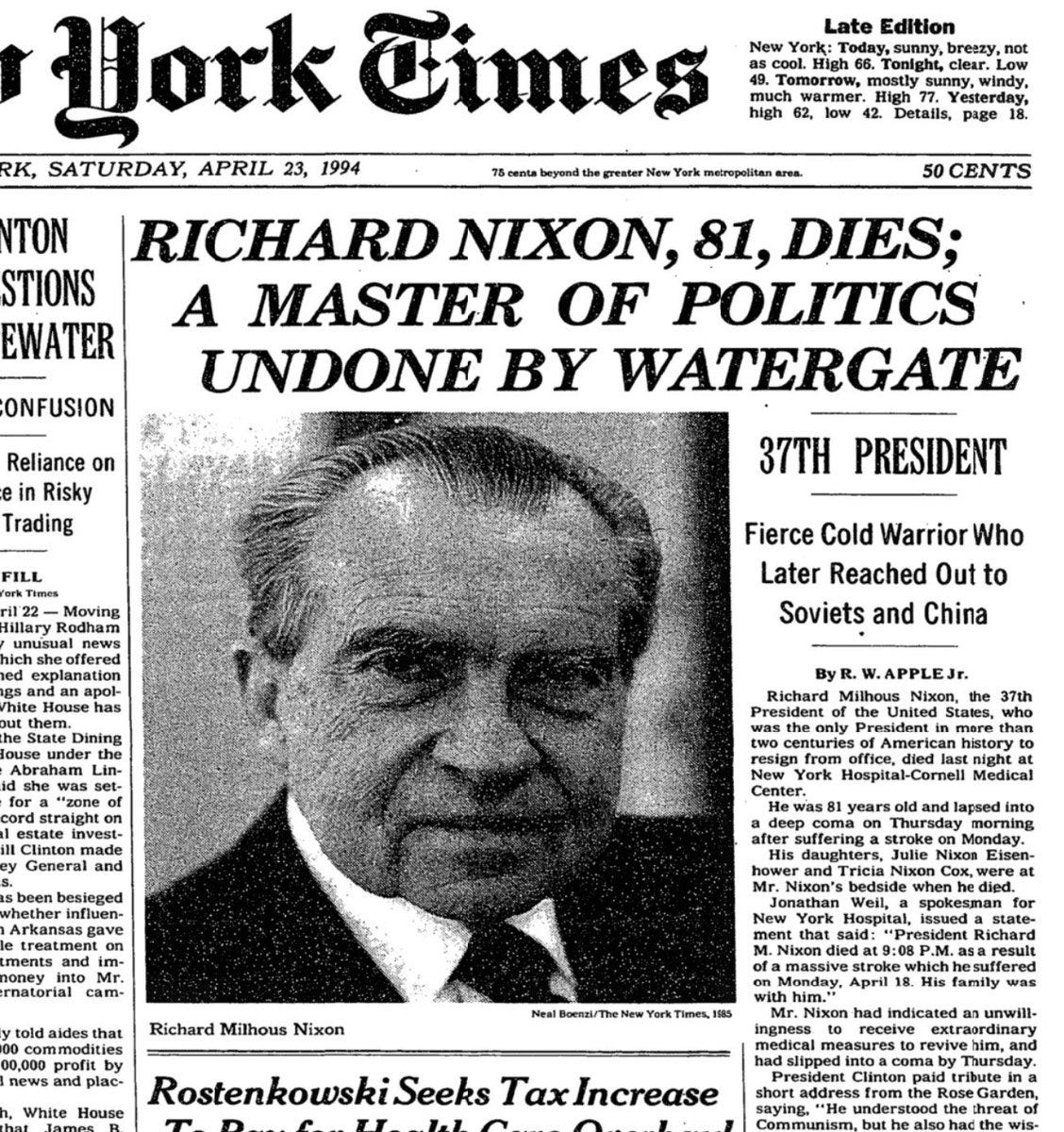

Richard Nixon unexpectedly died of a stroke on April 22, 1994, at the age of eighty-one, just fourteen months after his wife, Pat, died of lung cancer.

When I first got word that Richard Nixon had passed away, I was shell-shocked. The man had so much strength left in him, I thought he would live another decade. Nonetheless, he was gone, and I needed to attend to my duties as his friend.

My phone began ringing relentlessly almost immediately after I heard of Nixon’s passing. Reporters wanted quotes, TV shows wanted interviews, but all I wanted to do was be in a quiet place by myself, and grieve.

It would be another month or so before I actually had an opportunity to sit down and really reflect on my career with Richard Nixon, but I felt responsible as his closest political confidant before his death, to answer all of the questions that were asked of me, although I didn’t accept every interview request, purely out of deference to Nixon’s old rule.

In his final “fuck you” to the Washington establishment, Nixon ordered that his body not lie in state in the Capitol Rotunda, as had the remains of Johnson, Kennedy, Eisenhower, and Truman.

Richard Nixon was buried in Yorba Linda, California, on April 27, 1994. He was laid to rest on a plot next to his wife, Pat. He told me once that it felt fitting for him to be buried where he was born and where he grew up.

Henry Kissinger, Senator Bob Dole, former Presidents Ronald Reagan and Gerald Ford, President Bill Clinton, and Jimmy Carter attended the funeral to pay their respects.

The funeral service prompted some displays of emotion from men who rarely exposed their softer side.

Bob Dole was moved to tears during his eulogy, saying:

I believe the second half of the twenty-first century, will be known as the age of Nixon. He provided the most effective leadership. He always embodied the deepest feeling for the people he led . . . To tens of millions of his countrymen, Richard Nixon was an American hero — one who shared and honored their belief in working hard, worshiping God, loving their families, and saluting the flag. He called them the Silent Majority. Like them, they valued accomplishment more than ideology. They wanted their government to do the decent thing, but not to bankrupt them in the process. They wanted his protection in a dangerous world. These were the people from whom he had come, and they have come to Yorba Linda these last few days, in the tens of thousands, no longer silent in their grief. The American people like a fighter. In Richard Nixon they found a gallant one.

Dole then reminded us of a few very eloquent words Nixon once spoke:

You must never be satisfied with success. And you should never be discouraged by failure. Failure can be sad. But the greatest sadness is not to try and fail, but to fail to try. In the end, what matters is that you have always lived life to the hilt.

Dole proclaimed that Nixon was strong, brave, and unafraid of controversy, unyielding in his conviction—and that he lived every day of his life to the hilt.

In his closing remarks, Dole said:

The man who was born in the house his father built would become the world’s greatest architect of peace, the largest figure of our time whose influence will be timeless. That was Richard Nixon. How American. May God bless Richard Nixon, and may God bless the United States.

Former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger gave some details about how Nixon shaped foreign affairs:

He came into office when the forces of history were moving America from a position of dominance to one of leadership. Dominance reflects strength; leadership must be earned. And Richard Nixon earned that leadership role for his country with courage, dedications, and skill. The price for doing things halfway is no less than for doing it completely, so we might as well do them properly.

It was, however, the eulogy of President Clinton that Nixon would have enjoyed the most because it signified Nixon’s success in his final rehabilitation.

Clinton remembered Nixon as being a spirited politician:

He never gave up being part of the action. He said many times that unless a person has a goal, a new mountain to climb, his spirit will die. Well, based on our last phone conversations and the letter he wrote me just a month ago, I can say that his spirit was very much alive until the very end. On behalf of all four former presidents who are here; President Ford, President Carter, President Reagan, President Bush, and behalf of a grateful nation we bid farewell to Richard Milhous Nixon. May the day of judging President Nixon on anything but his entire life come to a close.

Henry Kissinger’s biographer, Walter Isaacson, summed it up better than most. He said that his experience with Nixon impressed him as:

A very complex man in everything he did, and there was a light side to him, there was a brilliance side to him, and there was a brooding side. And I think sometimes when he had the advisors appeal to his good side, he was able to do very good things.

- CNN Crossfire, April 27, 1994

Nixon’s death brought accolades from strange quarters.

Bill Clinton added:

He suffered defeats that would have ended most political careers, yet he won stunning victories that many of the world’s most popular leaders have failed to attain.

- April 4, 1994

Rev. Billy Graham:

He was one of the most misunderstood men, and I think he was one of the greatest men of the century.

- The Washington Post, April 22, 1994.

Boris Yelstin (Russian Leader):

One of the greatest politicians in the world.

- The New York Times, April 23, 1994

John Sears:

The picture I have of him is a mosaic, an image formed from a series of vignettes often so unexpected they can never be forgotten.

- Los Angeles Times, April 24, 1994

Nixon biographer Stephen Ambrose:

Nixon was the most successful American politician of the twentieth century.

- CBS This Morning, April 25, 1994

White House speech writer Ben Stein, whose father Herbert Stein was chairman of the Council of Economic Advisors under Nixon, recently said:

Let’s look at him with fresh eyes. Unlike LBJ, he did not get us into a large, unnecessary war on false pretenses. Unlike JFK, he did not bring call girls and courtesans into the White House or try to kill foreign leaders. Unlike FDR, he did not lead us into a war for which we were unprepared. He helped with a cover-up of a mysterious burglary that no one understands to this day. That was his grievous sin, and grievously did he answer for it. But to me, Richard Nixon will always be visionary, friend, and peacemaker.

Carl Bernstein:

Nixon defined the postwar era for America, and he defined the television era for America.

- The Washington Post, April 25, 1994.

President Jimmy Carter:

His historic visits to China and the Soviet Union paved the way to the normalization of relations between our countries.

- The Washington Post, April 23, 1994

Former President Ronald Reagan:

There is no question that the legacy of this complicated and fascinating man will continue to guide the forces of democracy forever.

- Dallas Morning News, April 23, 1994

Even his 1972 opponent George McGovern said:

Not too many people could psychologically withstand being thrown out of the White House. It takes an enormous amount of self-discipline that I had to recognize as remarkable.

- U.S. News, May 2, 1994

Not all remembrances of Nixon were favorable.

Gonzo Journalist Hunter S. Thompson wrote shortly after Nixon’s death:

If the right people had been in charge of Nixon’s funeral, his casket would have been launched into one of those open-sewage canals that empty into the ocean just south of Los Angeles.

Thompson, a lifelong hater of Nixon, amid the bile, also recognized Nixon’s special brand of resilience:

As long as Nixon was politically alive—and he was, all the way to the end—we could always be sure of finding the enemy on the Low Road. There was no need to look anywhere else for the evil bastard. He had the fighting instincts of a badger trapped by hounds. The badger will roll over on its back and emit a smell of death, which confuses the dogs and lures them in for the traditional ripping and tearing action. But it is usually the badger who does the ripping and tearing. It is a beast that fights best on its back: rolling under the throat of the enemy and seizing it by the head with all four claws.

- Rolling Stone, June 16, 1994

I summed up my one special memory of Nixon for Newsweek in April of 1994:

Working for Richard Nixon was like working for the mafia. You never really left and you never knew when you might be called on to perform a political chore.” Nixon achieved his goals of a more peaceful world and a lessening of tensions with America’s enemies. He built a government at once more compassionate and progressive than anyone would have imagined.

Driven from office by his terrible secrets; his approval of the CIA-Mafia plots to kill Castro, the Bay of Pigs, his reliance, along with virtually every national politician of the 1950s and 1960s, on mafia funding, the bribes he had taken from the Teamsters, his contretemps with the CIA, his knowledge of what really happened in Dallas and who was involved secured him a pardon in order to avoid prison and launch his greatest public comeback.

In 1986, the filmmaker Oliver Stone was producing his much heralded film on Richard Nixon. After conferring with Nixon associates Garment and Ziegler, Oliver Stone made John Sears one of his chief consultants on the project; recognition that Sears’s unique perspective on the Nixon psyche was vital.

Nixon’s friends feared the film would be a hatchet job. Instead, it is one of the most compelling films in the Stone ouevre presenting a surprisingly balanced portrait of the president. Actor Anthony Hopkins’s portrayal of Nixon was distinctly sympathetic. Stone even had Nixon standing up to a fictional conspiracy of rich men who had helped put him in office. Sears had shaped the movie as much as he had shaped the reporting of Woodward and Bernstein.

The release of the film was accompanied by a book comprising the screenplay and some essays, one of them by Sears. “Nixon,” Sears wrote, “was the loner produced by a nation of loners. That was the reason the country could not forgive Nixon for his illegal acts, even though others had done the same. We are a land of loners and our only protection is the law. Did I want him to escape at the time?” Sears asked rhetorically. “Yes. Did I think he would? No.”

But was Nixon, on balance, worth it for the country? “I would submit,” Sears wrote, “that if the world survives for a million years, perhaps its finest hour may be that in the last half of the twentieth century, when the power to blow up the world rested in the hands of a few men in two very unsophisticated and suspicious countries, we didn’t do it, and one American, Richard Nixon, moved the Cold —War away from permanent confrontation toward victory. How can any wrong that he did compare with that?

- Newsweek, April 22, 1994

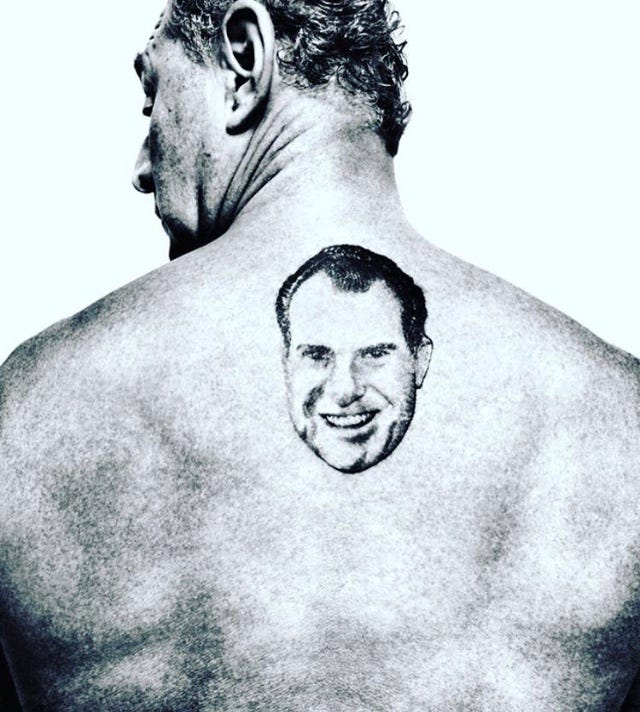

I, of course, am infamous for having a tattoo of President Richard Nixon on my back.

It's about the size of a grapefruit, and is really just a floating head between my shoulder blades. It is really not a political statement. When I see it in the mirror each morning it is a reminder that in life things do not go your way, and that when you get knocked down and when you are discouraged that you must get up off the mat and get back in the fight.

It was Richard Nixon who said: “The greatness comes not when things go always good for you. But the greatness comes when you're really tested, when you take some knocks, some disappointments, when sadness comes. Because only if you've been in the deepest valley can you ever know how magnificent it is to be on the highest mountain.”

It was also Richard Nixon who said: “A man is not finished when he is defeated. He is finished when he quits.”

Like my mentor Richard Nixon I will never quit.

Stone Cold Truth is your home for the most controversial and groundbreaking content from legendary political operative and cultural icon Roger Stone. Your subscription not only gives you first access to this information, but helps keep Stone Cold Truth alive.

Already subscribed and want to support Stone Cold Truth further, while getting more eyes on this important information? You can gift a subscription to a friend at the button below!

Comments are usually only open to paid subscribers -- but I want to hear what everyone has to say about this piece. I spent quite a bit of time putting this all together.

Agree - Nixon a great POTUS falsely maligned.